Nigeria has always been an interesting case. It’s the richly endowed country that is also home to some of the world’s poorest. It is where sprawling mansions exist in close proximity to slums. For some unexplainable reason, we have struggled to transform the mineral and human endowment into a better quality of life for all Nigerians. Inequality has been a permanent feature of our nation, the rich-poor divide being one of the most dispiriting.

Right from independence in 1960, when we seemed to replace one group of ‘lords’ with another, democratic politics and prebendal politics have been, what Richard Joseph, famously termed ‘one side of the same coin.’ Since 1987 when he made those observations in his book, ‘Democracy and Prebendal Politics In Nigeria: The Rise and Fall Of the Second Republic,’ politics has become the most lucrative business in the land and elevated government officials or anyone close to them, thereby furthering inequality.

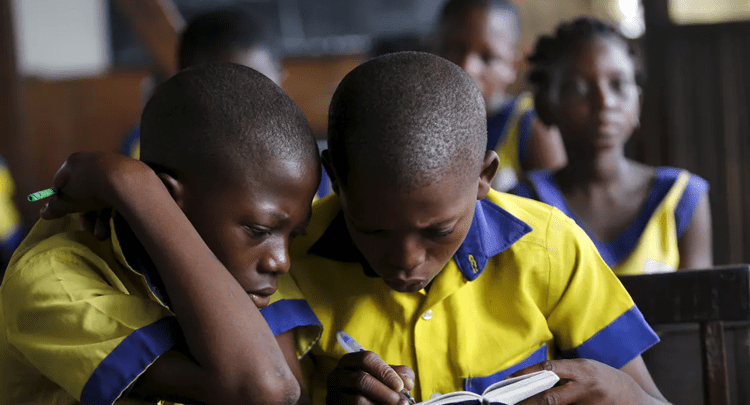

This elitist system leaves the majority struggling to get anything close to a decent living. The mansions, big cars, and private jets have mostly defined inequality, but private education has lately become another feature of the widening gap between the rich and poor.

Embraced first by the rich and the middle-class, private education is preferred because of the belief that it gives the student a shot at a good life. The idea is simple: a good education will grant access to the good life and open the door to the elite, pampered class. Until 20 – 30 years ago, public schools guaranteed this social mobility. I am in the generation that knew only public schooling, and I confess they were great in those days. I recall my time in Ilesa Grammar school in the early 80s and the fact that we had teachers from the Commonwealth, including those from Canada and India. My experience at the University of Ibadan from the mid-80s was no less enriching, but my children have known nothing but private schooling.

Most of the public secondary schools and universities in our time had the human and infrastructural capacity, which helped to provide quality at reasonable costs. However, years of misplaced policy, neglect, and mismanagement have turned most public schools into shadows of themselves. It looks as though policymakers and the schools stood still at a time of rapid technological changes and increasing demand for school places. Most of our tertiary first-generation institutions, like the University of Ibadan, are particularly worst hit, a lot of them looking worse than they did when some of us were there.

The constant closures due to protests and labour disputes worsen a bad situation. Students enrol now not sure of when they would graduate; the result being that sometimes, four-year programmes don’t finish in six or seven years. Even though there is no evidence to suggest that private schools are necessarily better, most parents are happy that their wards can at least finish academic programmes on schedule. I doubt, though, if any parent will question the quality in some of those private secondary schools and universities; otherwise, they won’t be attracting the level of patronage we are seeing.

The only danger, of course, is that the worsening state of public schools could further the inequality because hundreds of thousands of otherwise promising students are either denied access to quality education or when they manage to secure places, delayed for longer than necessary. Not only do many of those whose parents can afford private schools move faster, but they also end up abroad for graduate studies, further stretching their advantage. This is important because top companies appear to favour those with degrees from foreign schools in recruitment.

If the case of public schools was bad, Covid-19 threatens to make it worse. Lockdown learning is proving to be a measure of social inequality with the children from affluent homes and neighbourhoods enjoying full timetables and those from poorer families getting no home lessons. The lockdown imposed to curtail the spread of the virus means Churches, Mosques, businesses, and schools are closed.

This disruption to normal life has challenged leaders and exposed the shortcomings of those who are either not prepared for change or lack the capacity to cope with it. While some are complaining about the lockdown, others have embraced it and are utilising technology to keep their companies, schools, and churches going. It should worry us, especially where our children’s education is concerned, that those willing to embrace the change are making progress during lockdown while others wait. I am impressed that some secondary schools are organising tutoring online, using Zoom and WhatsApp and that some higher institutions like Babcock University have concluded plans to conduct semester examinations online. While this is commendable, and knowing that most public schools are ill-equipped for anything but in-person tutoring and supervision, the question is: would Covid-19 further inequality?

This is a question that should be of interest to us all since increasing globalization has made education a measurement of a nation’s ability to compete in the future. The world is shrinking every day, and top firms have a pool of talents from across the globe to pick from. You don’t even get in that pool unless you have received what can be considered standard education and training.

Nigeria already lags in this regard, falling behind other African countries in funding for research and development as well as research output. The frightening thing is that we even risk dropping further behind others in this all-important race due to our inability to adapt to meet the challenges of Covid-19. For instance, while most of our universities are closed, South African schools were quick to decide to move teaching online. You cannot but be impressed with the detailed arrangements.

Telecoms companies were persuaded to make 30Gb free data available to students for a month to enable them to attend online classes via Zoom or Microsoft Teams. Some schools made laptops offers to students who needed assistance in that regard. The result of such quick thinking is the students have only missed the few weeks it took for the schools to set up and move lectures online. This is where the approach taken by the likes of Babcock is commendable and why the Federal Ministry of Education, as well as the National Universities Commission (NUC), must rethink their policy on tertiary education in Nigeria.

Covid-19 has shattered social relationships as we know it and may alter the way we worship, do business or study permanently.

Forward-thinking policymakers must ask: what if restrictions on social gatherings last longer than anyone can imagine? If the lockdown continues into 2021, for instance, would our tertiary institutions remain locked till then? We need to learn from those who are adapting in an exemplary fashion and act fast. Some institutions are already making preparations on the assumption that Covid-19 is the new normal, and in the absence of anything to prove otherwise, that should be a model for everyone. The California State University, America’s largest four-year college system, announced last week it is cancelling most in-person classes in its 23 campuses from September. As we approach the next school session, others may well follow the lead. The University of Johannesburg last Wednesday held a virtual graduation ceremony, again signalling the readiness to work with this new normal. With available technology, nothing should stop business meetings, church service, and tutoring.

Nigeria lags behind many African nations because successive governments and the NUC have failed miserably with policies on tertiary education, but Covid-19 presents an opportunity to course-correct. University teaching staff have always complained about funding, and their arguments may be valid because others are outspending Nigeria in research funding. Federal and state governments, Tetfund and university administrators have failed students but Covid-19 is a chance to redeem the situation. The most puzzling of all is the continued relevance of Tertiary Education Trust (Tetfund), which among other things, was founded to ‘promote cutting-edge technologies, ideas and organizational skills in education, and ensure that projects are forward-looking as well as responding to present needs.’

It has to be said though that Tetfund has done creditably well by promoting quality scholarship through foreign post graduate scholarships, and conferences that expose lecturers to the most recent theories, practices and skills. However, for as long as students in our higher institutions are still forced to submit academic papers and thesis in print; If they have to print out copies of PowerPoint to read from when making presentations; if lockdown means schools are on break until further notice; If instruction and supervision of students cannot hold without physical contact, then Tetfund is failing in one of its most important goals. Future interventions should be directed at building IT infrastructure to enable more convenient and effective learning as well as re-training of teaching staff to make them IT-compliant.

Governments at the federal and state levels, which fund tertiary education should understand the enormity of the problem and increase budgetary allocation to the sector to enable our schools compete on the global stage. Budgetary allocations usually signal the intention of policymakers and recent figures show other African countries have a better understanding of the importance of the place of education in national development. Available data shows that South Africa’s allocation to educated in 2018 was 6.16% of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), while Ghana managed 3.99% for that year. The World Bank and the United Nations Education and Scientific Organisation (UNESCO) do not have the figures for Nigeria but the federal allocation to education in 2018 was N102.9 billion, which amounts to well below 1% when the Naira rate and the GDP rate for that year are factored in. Lastly, university administrators must also re-strategise, possibly by building businesses on research and development instead of selling bread and bottled water. With a strong partnership with corporate Nigeria, they can generate more funds to invest in IT. Only a few public universities have the required infrastructure to even admit online so, to ask for remote teaching would be asking for too much. It sounds daunting, but there is no other way to compete with the rest of the world, especially if we are to address the inequality between private schools and their public counterparts.

Akin Olaniyan is a communication specialist and PhD candidate at the University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg